By ELISABETH ROSENTHAL

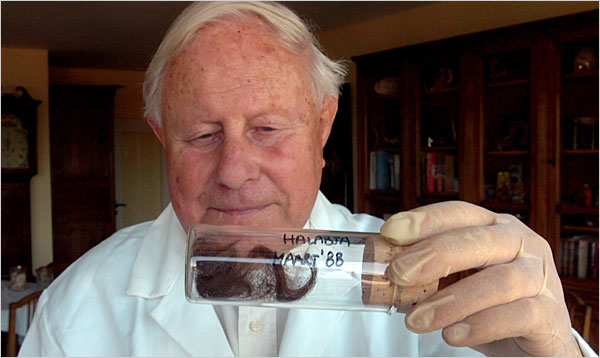

GHENT, Belgium — For 18 years, Dr. Aubin Heyndrickx has tended the sealed jars containing strands of hair and scraps of clothing he gathered from a dead woman's body.

Collected in Halabja, one of many Kurdish towns in northern Iraq that were attacked with chemical weapons by Saddam Hussein's army in 1988, the jars have been stored in a blue plastic drum in his lab ever since, waiting.

Now, as prosecutors prepare to try Mr. Hussein in Baghdad on charges of genocide against the Kurds, Mr. Heyndrickx, who has retired as director of the toxicology lab at the State University of Ghent, would like the material to be analyzed. "May I insist these proofs are mentioned at the trial?" the doctor asks.

He is one of a small group of doctors, scientists and Middle East experts who have studied chemical weapons use by Iraq against its Kurdish citizens in the 1980's. They are dusting off evidence and trying to collect new data in an effort to define the scope of a distant tragedy that is only now coming under scrutiny in court.

But proving that the victims died from chemical weapons is a daunting task: all the firsthand evidence was gathered nearly 15 years ago, and many records have been lost or destroyed. The attacks occurred in remote areas where little testing was available.

"Unfortunately, we'll never know how many people were killed or exposed," said Dr. Joanne al-Talabani, who for the past three years has visited the area to study the long-term health problems of Kurdish children exposed in the attacks, including scarred lungs and eyes as well as birth defects. "There are no medical records from that time — none. Most people can't remember: they were delirious, running, in shock."

The study of chemical weapons is an arcane, imperfect corner of forensic science, where lab results and doctors' physical exams yield hints of exposure, but rarely direct legal proof. Chemical weapons break down quickly in the environment or in the body, and scientists are unsure what, if any, tracks they should look for nearly 20 years after the fact.

Mr. Hussein is already on trial in Baghdad in another case, involving the execution of 148 Shiite men and youths after an abortive assassination attempt against him in Dujail in 1982. That trial, which began eight months ago, moved into closing arguments on June 19, with the prosecution demanding the death penalty for Mr. Hussein.

Iraqi prosecutors have said they expect the so-called Anfal case — the term, meaning "spoils" in Arabic, was the code name for the Iraqi military's attacks on the Kurdish villages — to begin this summer or in early autumn. The formal indictment focuses on attacks in 1988 that are suspected of killing 50,000 Kurdish villagers, though Kurdish leaders say that perhaps three times as many Kurds died in the attacks.

The Anfal trial, which includes the chemical weapons charges, "will be the most important public reckoning, but in court you can't just say, 'I know it happened,' " said Alastair Hay, a professor of chemical pathology at the University of Leeds in England who has studied soil samples from Kurdistan. "You need solid, irrefutable scientific evidence. But it's very difficult to establish something like nerve-gas exposure at this stage. I can't tell you how frustrating this is, since nothing concrete has ever appeared."

An American-led team of forensic specialists working for the Iraqi court spent weeks examining one mass grave of victims at Hatra, near Mosul, a northern city. But those deaths, including women and children, were the result of gunfire at the grave site, not chemical weapons.

Almost all experts now contend that Mr. Hussein's armies used chemical weapons against Kurdish civilians: mustard gas and probably two nerve agents, tabun and sarin. C.I.A. documents refer to chemical weapons use, and former top Iraqi military officers have confirmed the suspicion, said Joost Hiltermann, a former senior researcher at Human Rights Watch whose exhaustive book on the topic is scheduled to appear in 2007. Mr. Hussein has repeatedly denied the allegation.

Iraq's use of chemical weapons, banned by the 1926 Geneva Convention, against Iranian soldiers during the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-88 was confirmed in a series of United Nations verification reports. Iran is still monitoring 30,000 people who were exposed.

But it is more complicated to tally the effect of such banned weapons against the Iraqi Kurds. Estimates of the number of victims range from the thousands to the hundreds of thousands.

"Twenty years later it is difficult to prove on the basis of physical evidence, but the total picture in my eyes doesn't leave any doubt that it occurred," said Dr. Jan Willems, a retired professor of environmental medicine at Erasmus Hospital in Brussels. He said he examined several Kurdish patients who had traveled to Europe shortly after gas attacks in 1988, displaying burns associated with mustard gas.

Testimonials are plentiful: Iraqi Kurds have consistently described how, in 1998, Mr. Hussein's warplanes delivered bombs filled with sweet-smelling gases to put down the Kurdish insurgency, with harrowing results.

Shorsh Haji, a researcher who now lives in London, still recalls the night of Feb. 22, 1988, when the bombardment went on for two hours near his home in the Jafati Valley; he assumed it was conventional weapons. When he emerged in the morning, he discovered otherwise. "People on the streets were coughing, vomiting, their eyes were weeping," Mr. Haji said. "Some had blisters on their legs and under their arms."

"A family of five down the road had died instantly," he said.

The United Nations did not investigate charges of chemical use against the Kurds in those early days, when it would have been far easier to prove, because it was regarded as an internal Iraqi conflict, Mr. Hiltermann said.

The world viewed with some skepticism testimonials from Kurdish guerrillas. At the time, Mr. Hussein was an ally of the United States, and the components of his chemical arms were often supplied by European businessmen.

On the medical side, proof of the attacks is scant because Kurds were afraid to go to local Iraqi hospitals, where doctors had been told not to treat them, said Dr. Talabani, who emigrated in 1977 and is now a pediatrician with the British National Health Service.

Those who slipped over the border to Iran for diagnosis and treatment often destroyed their medical records documenting chemical exposure before returning, for fear it would open them to persecution, the doctor said. Also, while Iran quickly sent hundreds of its soldiers to hospitals in Belgium and Austria, which helped prove attacks there, only a very few Kurds got out for evaluation.

In the days after an attack, mustard gas exposure is relatively easy to document. Used extensively in World War I, it causes unusual blistering burns of the skin as well as severe irritation of the eyes and lungs. Breakdown products of the gas can be detected for weeks in the urine, making recent exposure simple to prove in a sophisticated lab.

The use of nerve agents like tabun and sarin, the chemical used in the Tokyo subway attacks in 1995, is far trickier to prove because these gases are short-lived and deadlier. "Mustard leaves lots of physical evidence," Mr. Hiltermann said. "With sarin, people die or get better fast, so it's very difficult to prove."

Despite charges by Kurdish groups of mass killings by chemical weapons in 1988, the only specific physical proof is four soil samples collected in 1992, from two bomb craters near the Kurdish village of Birjinni, by a team from Middle East Watch and Physicians for Human Rights that included Mr. Hay.

After meticulous testing at the Porton Down Naval Laboratory in England, two samples were found to contain degradation products of mustard gas, and two showed breakdown products of sarin. Other attempts to analyze soil samples after the fact have all turned up negative.

"We looked in the bomb crater itself — in one case under a piece of shell — where concentrations were higher," Mr. Hay said.

The long-term health problems of patients from the area offer indirect evidence of chemical weapons use. But survivors tend to have vague conditions, like chronic bronchitis or pain, that have many other possible causes. Mustard gas causes breathing problems, but no studies have been performed to define the link between exposure to nerve gases and long-term health problems, experts said.

Dr. Talabani said that more than 300 patients she has been studying, who were exposed in childhood, seemed to have an "extremely high incidence of illness." She determined exposure according to the history patients relayed: a history of chemical burns indicated exposure to mustard gas, while lack of coordination or seizures after an airstrike indicated a nerve agent.

"Unfortunately little is known because this is the first group studied," Dr. Talabani said. "There are very severe breathing problems, skin problems and eye problems, such as corneal scarring that has already required transplants."

Over the years, a large number of former Iranian soldiers and a smaller number of Kurds who say they were exposed to chemical weapons have been seen at European hospitals with a broad range of medical complaints. There are no blood tests that serve as markers for chemical exposure, though scientists like Mr. Hay say such "tracks" could be discovered with research.

"Diagnosis was based on clinical history and signs and symptoms," Mr. Willems said.

Because of the lack of hard data and the imprecise testing, there is some disagreement about how many people were affected and what chemical compounds were used.

Dr. Heyndrickx says he believes that the Iraqi Army used cyanide and biological toxins as well as mustard gas and sarin, making him somewhat of a maverick in the field, since most other scientists feel that the evidence doesn't support this claim.

Still, he was one of the few Western experts in Halabja just after the attack, and the samples in his lab, particularly the clothing, could still provide valuable clues if they were properly sealed and stored, Mr. Hay said.

"People now tend to say it's obvious that Saddam committed crimes, but for legal and international standards we need to have evidence," said Mr. Haji, the researcher, whose testimony has been accepted by the court. "Only then can people who were exposed be compensated."